By Stephen P. White

There is something appropriate about the date of Thanksgiving. I don’t mean that the fourth Thursday of November has something special in itself, but rather that it invariably falls in the last week of Ordinary Time. Thus, our secular holiday coincides with the close of the liturgical year. This creates an interesting juxtaposition, in which a celebration of God’s generosity and blessings occurs amid a liturgical barrage of readings about the end of the world.

Take, for example, today’s readings: Thursday of the 34th Week of Ordinary Time. In the first reading, some men burst into Daniel’s house, denounce him to the king, and have him thrown into the lions’ den. We know the story ends well for Daniel, but not for his accusers, nor for their wives, nor for their children. “Before they reached the bottom of the den, the lions overpowered them and crushed all their bones.”

The Gospel of the day is taken from St. Luke, and it is apocalyptic from beginning to end. “Jesus said to his disciples: ‘When you see Jerusalem surrounded by armies, know that its desolation is at hand,’” and from there everything gets worse: Woe to the pregnant women!, people falling by the sword, being trampled or dying of fright.

The Lord promises to return in glory and exhorts the faithful to stand firm, but the whole scene sounds terrible, and it is clear that Jesus wants it to sound terrible. When the Son of God warns of a “great calamity,” “wrathful judgment,” and “nations in dismay,” it is wise to take it seriously.

In the United States, of course, we normally hear the readings proper to the Thanksgiving Day, and not those of Thursday of the 34th Week of Ordinary Time, and those readings are much less likely to ruin the appetite before the turkey goes into the oven. The Thanksgiving Day readings are centered on gratitude for God’s blessings.

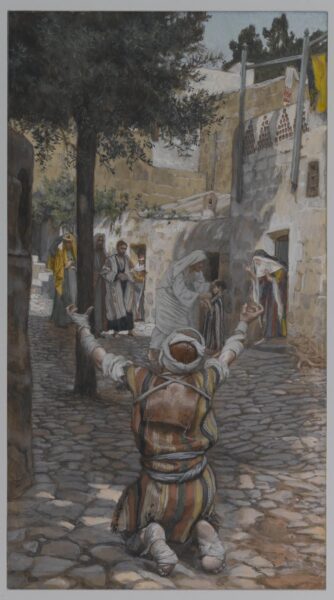

We hear from the book of Sirach how the Lord cares for the child even in the womb, and about the joy, peace, and constant kindness of the Lord. We hear from St. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians how God pours out his grace and all spiritual gifts. In the Gospel (also from St. Luke), Jesus heals ten lepers and only the Samaritan among them returns to give thanks: “Rise and go; your faith has saved you.”

No lions, crushed bones, terrible calamities, or wrathful judgment. Just grace, healing, and glory to God for the blessings received.

This juxtaposition between these two sets of readings, so different in tone, might seem jarring, even contradictory. But Christians know that the futility of this world, which is passing away—both in the transience and material corruption we experience every day of our brief lives, and in the tumultuous, terrible, and undoubtedly awe-inspiring end that will come—in no way negates the goodness of this world or of this present life.

These are extraordinary gifts, given by a loving God, for our use and enjoyment. He made this world for us, and made us capable of enjoying it.

Of course, as the stubborn and ungrateful race that we are, we often spoil these gifts. We worship the gift instead of the Giver. We lose sight of the proper end to which all these wonderful means are ordered. We hoard and waste his gifts, which are two forms of ingratitude.

Even some of us teach ourselves to despise his gifts in a misguided attempt to compensate for our tendency toward excess. Discipline in virtue is something good and necessary for all, and every saint is an ascetic in some sense. The world may hate us, but hating the world in response is to fail to understand the gratuity of its Creator, an affront to the magnificence of the Incarnation.

On this last point, Advent—which always follows so closely after Thanksgiving—is above all a season in which we prepare to rejoice in the great mystery of the Incarnation, the definitive rebuttal to the ancient heresies of the Gnostics and Manicheans. The world was not only made by a God who declared Creation “very good,” but was made in such a way that He himself could enter into it. This world may be passing away, but it is in this very world that the Child of Bethlehem was born.

And that is a delightful thought, even here, at the end of the liturgical year, among the bare trees and shortening days.

As I was saying, the arrival of Thanksgiving in these apocalyptic days is timely. Banqueting at the end of the world may seem impious, spiritually akin to fiddling while Rome burns. But giving thanks should not be reserved only for times of peace and prosperity. If the whole world were burning around us, it would be right and necessary for Christians to give thanks to God for all that he has done for us.

The world is passing away, and we can be at peace letting it go. We can give thanks to God for his gifts, even as we offer them back to him. Gratitude is not just for good times, and whether the Mass readings speak of condemnations and sufferings or of blessings and consolations, our response must be the same: “Let us give thanks to God.”

I wish you a very blessed and happy Thanksgiving Day.

About the author:

Stephen P. White is executive director of The Catholic Project at The Catholic University of America and a fellow in the Catholic Studies Program at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.